| 30/04/2025 | |

| Cattolica International - 30 aprile 2025 |

Demographers are not clairvoyants, but they have the expertise to anticipate population growth and ageing trends long before they unfold. Not only that, but they can also interpret numbers and trends to reveal the spirit of the times. Above all, they recognise that being 20 today is vastly different from 1970, when young people were more numerous, and opportunities seemed more abundant. To discuss these and other themes, we interviewed Professor Alessandro Rosina.

You coined the term “dejuvenation,” which has also appeared in international journals, such as the Journal of Italian Studies, where you explain1: “Dejuvenation is considered in two dimensions:

- the reduced share of young people (aged 0–29) in a country and the decline in the qualified presence of young generations in society and the economy. It is an unprecedented phenomenon, as historically young people have always been the majority in all populations (Livi Bacci 2011);

- the main source of economic growth and a major push for social innovation.” Thus, dejuvenation is not simply a way to describe the progressive ageing of the population but a weakening of the perspective and expectations that youth typically bring toward the future.

Could you tell us more about this phenomenon?

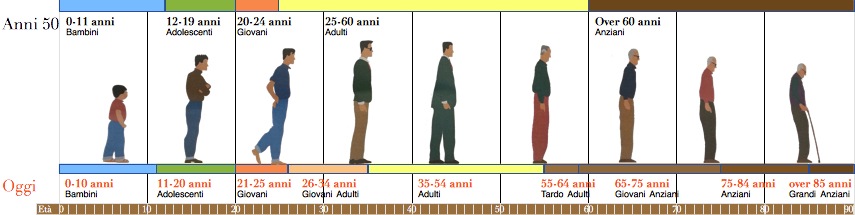

The term “ageing” describes the increasing number of older adults, while “dejuvenation” highlights a different yet complementary aspect – namely, that as the elderly population grows and lives longer, the number of young people is declining. This occurs when fertility rates fall below two children per woman, the threshold needed for generational replacement. When this happens, each new generation is numerically smaller than the previous one, and over time, this gap widens.

The fact that younger generations are smaller than their predecessors is a completely new situation because, in the past, fertility rates were consistently above two children per woman. Italy fell below two children per woman in the late 1970s and reached below 1.5 by 1984. With such a low birth rate, even immigration flows were no longer sufficient to make up for the decline in births. Therefore, dejuvenation and the ageing of the population have an impact not only in terms of numbers but also socially and politically: a society with fewer young people loses their energy and enthusiasm, experiences a decline in youth presence in the workforce, and sees a reduction in their electoral power and influence in collective decisions about their country’s future.

This is here the paradox emerges: according to basic economic principles, scarcity should increase value and investment. Yet, despite fewer young people, Italy and other mature economies have not significantly increased investments in education, housing, or innovation – the very areas that would support youth.

Another key factor is longevity: thanks to improvements in health and well-being, people are living much longer than before. But what impact does this have on society?

Longevity is a good thing, but declining birth rates should not be seen as an unavoidable fate. We must balance longer lifespans with sustainable birth rates to ensure a higher quality of life. If older adults have adequate pensions, care, and support, they can remain self-sufficient, contributing to society while reducing social costs. But to make this possible, we need resources that should come from new generations entering the workforce. However, if few young people are adequately trained and valued, the workforce shrinks, and they cannot sustain on their own the unavoidable expenses such as pensions and healthcare for the elderly. So, how do we compensate for the lack of resources typically provided by young workers? Unfortunately, the savings often come at the expense of young people themselves and their education. This illustrates how dejuvenation has both a qualitative and quantitative dimension: by investing in qualitative actions that improve the condition of young people, helping them develop skills to innovate and create new jobs through their ideas, we inevitably create a positive quantitative impact.

Let’s talk about education systems. How do you see them changing in the future?

Future education delivery must consider new technologies and a new way of understanding humanity. As new generations’ learning styles evolve, the traditional asymmetrical model, where knowledge flows one way from teacher to student, can no longer function as it has. Young people need to learn using the same technologies they use daily, applied within the educational context as well. Moreover, it’s no longer valid to think that there is only one phase of life dedicated to learning or that what you study once will suffice forever: a long active life and lifelong learning go hand in hand.